| ||||||||||

Ilona Fűzéková poses with painter Sayuki Matindiko and Beatrice Peter, wife and son of the painter Peter Martin who passed away in 2005.

from

| ||||||||||

We have many organization operating under the guise Tanzania artst but their money will not help the real life of Tanzanian artist. By helping Tanzania Artst directly involve you directly to assist Tanzania Tanzania life and future. Contact them and make part of your friend. One love, we love you.

Saturday, July 14, 2012

Sayuki Matindiko and His son Stamili Sayuki

Brek newzzz...The 7th Berlin Biennale––more discussions than ever before

From http://www.berlinbiennale.de/blog/en/comments/the-7th-berlin-biennale-more-discussions-than-ever-before-32176

The Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art has become a format providing a space for curatorial concepts beyond the mainstream production of contemporary art and culture. By choosing the artist Artur Żmijewski as the curator of the 7th Berlin Biennale, the Berlin Biennale once again demonstrated itself as a space for action and experimentation. Żmijewski and his pick of associated curators, Voina and Joanna Warsza, were particularly interested in strengthening the social impact of art and artists in order to manifest their responsibility towards the processes of social change. With more than 120,000 visitors, it was at twelve sites in Berlin and in Eisenhüttenstadt that the 7th Berlin Biennale negotiated art as a tool for social transformation by presenting a range of attempts of influencing politics directly.

For the first time in its history, everyone could visit the Berlin Biennale free of charge—a novelty that helped to reach audiences who normally do not respond to art institutions. Many visitors used the chance to visit the 7th Berlin Biennale more than once, hence following its process-based development. A newspaper informed about important issues around the 7th Berlin Biennale and offered texts on the participating artists and projects.

Already before its opening, the 7th Berlin Biennale generated a broader media interest than any previous edition. More than 1,000 articles in the daily news and specialized press reported on the event more extensively than ever before. In correspondence with the curatorial demand, the 7th Berlin Biennale’s content was no longer solely negotiated in the art field—the remarkable resonance to it exceeded the usual specialized publications and comprised not only national (Tagesschau) but also international press coverage such as Al-Jazeera and CNN.

The aim for direct political influence led to the process-based character of the 7th Berlin Biennale. While it did not begin with the mere installation of artworks in the gallery space, it will also not end by simply shutting the doors and cleaning everything up. It was months before the official opening on April 26, 2012 that one of the projects had already started: Martin Zet’s campaign to drop off Thilo Sarrazin’s best-seller Deutschland schafft sich ab at so-called collection points all over Germany triggered a heated public debate that, instead of focusing on the racist content of the best-seller itself, protested wildly against the alleged intent of a book burning.

Correspondingly, the processes that this year’s Berlin Biennale initiated are far from completed with the closure of the event on July 1, 2012. In the following months a number of solidarity partners are going to continue with a series of actions, such as in the context of the upcoming steirischer herbst or the Swiss Institute in Rome. In addition, there are projects that were started as part of the 7th Berlin Biennale but will continue beyond it. Both the documentation of the exhibition and its projects and the discussions around it will continue to be accessible on the Berlin Biennale website. The newspaper Self # governing by Marina Naprushkina communicates scenarios of an alternative future to the citizens of Belarus. In the course of the 7th Berlin Biennale its first edition was distributed all over Europe as well as secretly to hundreds of homes in Belarus. It remains to be seen which impulses and changes Naprushkina’s drawings will initiate.

The project Berlin-Birkenau is a similar situation, for it will have an effect on the landscape of Berlin over the next decades. Łukasz Surowiec displaced several hundreds of birches from the environment of the former concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau to the landscape of Berlin. Now, these trees grow as living, decentralized monuments in schoolyards, parks and private spaces such as gardens and balconies. A further example of the flexible framework, which is needed for this type of exhibition, is the Peace Wall by Macedonian artist Nada Prlja. The wall at the southern end of Friedrichstraße highlighted the obvious, yet rarely pronounced processes of social segregation. The artist went to the site and discussed with business people, local residents, district politicians and the media. Although an application of urgency by the district council Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg to take down the wall was rejected, Prlja ultimately conceded to an early dismantling of the Peace Wall. Likewise the wall might have led to collectivizing the neighborhood and articulating own demands. In a similar way as regarding Martin Zet, with this project the Berlin Biennale entered the unstable territory of public debate by making a provocative statement—a risk whose results one could hardly foresee or control.

The 7th Berlin Biennale had an impact on district politics and the landscape of the city, on debates about collective memory and even on the executive board of one of the largest arms manufacturers in Germany. In 2011 the Federal Security Council confirmed the sale of tanks to Saudi-Arabia, which since March 2011 has been directly involved in the destruction of the Arab Spring. The group of art activists, Center for Political Beauty, used a website and billboards in Berlin-Mitte to post a wanted-call aiming for the arrest of the proprietors who cannot be sued for their dealings. In the course of this initiative one of the members of the executive board publicly denounced the trade with Saudi-Arabia upon which he was dismissed from the executive board.

In addition to Self # governing by Marina Naprushkina, Paweł Althamer’s collective performance Sunbeam was a direct response to the problem of participation in Belarus. Althamer mobilized 250 people who wore golden suits and marched at dawn towards the government palace in Minsk, a city in which it can be an illegal assembly if some friends happen to accidentally meet in the street. The journey of an oversized key sculpture from the refugee camp Aida near Bethlehem to the 7th Berlin Biennale provided an occasion to address the marginalization of the Palestinian narrative within the German public. With the passport and postal stamps for Palestine that Khaled Jarrar distributes worldwide as part of his project State of Palestine, the artist suggests the existence of a hitherto utopian state while at the same time transcending stable national aspirations.

Among the numerous discussions of recent years about the relationship between art and social responsibility, Artur Żmijewski’s Berlin Biennale represents a decisive practical step forward, not least also in terms of addressing the kind of self-deception that “critical” art is subjected to. For where does critical art really make an impact? Does it change the regional grievances it points out, or does it matter rather in the western centers where it is not only shown, but economically profitable? The Institute for Human Activities, which was co-founded by the artist Renzo Martens, attempts to turn the tables by displacing art production to places where gentrification would actually be desirable. A program of workshops and stipends on a plantation in the Congo wants to encourage local residents to benefit from the global art market by producing their own artworks. The Institute launched its five-year plan of activities with a seminar conducted as part of the 7th Berlin Biennale.

These were just a few concrete examples among the many other thought-provoking 7th Berlin Biennale projects. The Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP), initiated by Israeli-Dutch artist Yael Bartana, calls for a return of more than 3 million Jews to Poland, opening up questions about issues of co-existence both regarding Europe and Israel and the Middle East. Held at the Hebbel am Ufer (HAU 1), the First International Congress of the JRMiP developed a concrete platform and demands for the movement. The New World Summit by Dutch artist Jonas Staal was another contribution to the culture of political debate. Organized at Sophiensaele, this event brought together political and legal representatives of organizations marked on international terrorist lists. Discussing the undemocratic methods with which democracies exclude certain interests from their systems of representation, the alternative “parliament” assessed possibilities for introducing a radical form of democracy in Europe.

Political engagement is always connected to the problem of social responsibility. Theater that Acts was developed in cooperation with the Hebbel am Ufer and one of its performances, Illumination, by the theater group Krétakör around Hungarian director Árpád Schilling, pledged for understanding actors as political people. The actors of Krétakör see themselves as active members of society who transcend “façade art” (Marcin Śliwa in the reader Forget Fear).

As part of our contemporary society it is particularly the Occupy movements (started in 2011 with M15 and Occupy Wall Street) that represent the demand for social empowerment and participation on a global scale in a media savvy manner. Throughout the duration of the 7th Berlin Biennale, representatives from these different international groups practiced their forms of protest and strategies of involvement on the ground floor of KW. While the institution initially only offered the space, over the course of the exhibition this partnership grew into the desire not only to address the visitors of the exhibition as members of society, but also to transform the institution as a mediator between art and society into a “horizontal” structure––an example of the process-based and self-critical methods with which Artur Żmijewski and his associated curators made pivotal contributions to contemporary discussions around exhibition production.

The 7th Berlin Biennale did not pursue the type of curatorial concept that communicates a particular idea through a physical arrangement of artworks in a space. Rather it was the question how art can allow citizens to influence reality and foster critical attitudes in society. Both the activists from the movements as well as the participating artists tried to position themselves in relation to concrete political and social concerns in order to contribute to situating art within the field of contemporary politics. At several moments during the 7th Berlin Biennale it became apparent how uncomfortable both art’s debate with itself and its confrontation with political reality can be. For an attitude of artistic and political responsibility is always accompanied by skepticism, disagreement, risk, confrontation, and possible failure. The 7th Berlin Biennale prompted us to leave behind our feelings of discomfort and fear of confrontations and change in order to face the challenge of social transformation.

The Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art has become a format providing a space for curatorial concepts beyond the mainstream production of contemporary art and culture. By choosing the artist Artur Żmijewski as the curator of the 7th Berlin Biennale, the Berlin Biennale once again demonstrated itself as a space for action and experimentation. Żmijewski and his pick of associated curators, Voina and Joanna Warsza, were particularly interested in strengthening the social impact of art and artists in order to manifest their responsibility towards the processes of social change. With more than 120,000 visitors, it was at twelve sites in Berlin and in Eisenhüttenstadt that the 7th Berlin Biennale negotiated art as a tool for social transformation by presenting a range of attempts of influencing politics directly.

For the first time in its history, everyone could visit the Berlin Biennale free of charge—a novelty that helped to reach audiences who normally do not respond to art institutions. Many visitors used the chance to visit the 7th Berlin Biennale more than once, hence following its process-based development. A newspaper informed about important issues around the 7th Berlin Biennale and offered texts on the participating artists and projects.

Already before its opening, the 7th Berlin Biennale generated a broader media interest than any previous edition. More than 1,000 articles in the daily news and specialized press reported on the event more extensively than ever before. In correspondence with the curatorial demand, the 7th Berlin Biennale’s content was no longer solely negotiated in the art field—the remarkable resonance to it exceeded the usual specialized publications and comprised not only national (Tagesschau) but also international press coverage such as Al-Jazeera and CNN.

The aim for direct political influence led to the process-based character of the 7th Berlin Biennale. While it did not begin with the mere installation of artworks in the gallery space, it will also not end by simply shutting the doors and cleaning everything up. It was months before the official opening on April 26, 2012 that one of the projects had already started: Martin Zet’s campaign to drop off Thilo Sarrazin’s best-seller Deutschland schafft sich ab at so-called collection points all over Germany triggered a heated public debate that, instead of focusing on the racist content of the best-seller itself, protested wildly against the alleged intent of a book burning.

Correspondingly, the processes that this year’s Berlin Biennale initiated are far from completed with the closure of the event on July 1, 2012. In the following months a number of solidarity partners are going to continue with a series of actions, such as in the context of the upcoming steirischer herbst or the Swiss Institute in Rome. In addition, there are projects that were started as part of the 7th Berlin Biennale but will continue beyond it. Both the documentation of the exhibition and its projects and the discussions around it will continue to be accessible on the Berlin Biennale website. The newspaper Self # governing by Marina Naprushkina communicates scenarios of an alternative future to the citizens of Belarus. In the course of the 7th Berlin Biennale its first edition was distributed all over Europe as well as secretly to hundreds of homes in Belarus. It remains to be seen which impulses and changes Naprushkina’s drawings will initiate.

The project Berlin-Birkenau is a similar situation, for it will have an effect on the landscape of Berlin over the next decades. Łukasz Surowiec displaced several hundreds of birches from the environment of the former concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau to the landscape of Berlin. Now, these trees grow as living, decentralized monuments in schoolyards, parks and private spaces such as gardens and balconies. A further example of the flexible framework, which is needed for this type of exhibition, is the Peace Wall by Macedonian artist Nada Prlja. The wall at the southern end of Friedrichstraße highlighted the obvious, yet rarely pronounced processes of social segregation. The artist went to the site and discussed with business people, local residents, district politicians and the media. Although an application of urgency by the district council Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg to take down the wall was rejected, Prlja ultimately conceded to an early dismantling of the Peace Wall. Likewise the wall might have led to collectivizing the neighborhood and articulating own demands. In a similar way as regarding Martin Zet, with this project the Berlin Biennale entered the unstable territory of public debate by making a provocative statement—a risk whose results one could hardly foresee or control.

The 7th Berlin Biennale had an impact on district politics and the landscape of the city, on debates about collective memory and even on the executive board of one of the largest arms manufacturers in Germany. In 2011 the Federal Security Council confirmed the sale of tanks to Saudi-Arabia, which since March 2011 has been directly involved in the destruction of the Arab Spring. The group of art activists, Center for Political Beauty, used a website and billboards in Berlin-Mitte to post a wanted-call aiming for the arrest of the proprietors who cannot be sued for their dealings. In the course of this initiative one of the members of the executive board publicly denounced the trade with Saudi-Arabia upon which he was dismissed from the executive board.

In addition to Self # governing by Marina Naprushkina, Paweł Althamer’s collective performance Sunbeam was a direct response to the problem of participation in Belarus. Althamer mobilized 250 people who wore golden suits and marched at dawn towards the government palace in Minsk, a city in which it can be an illegal assembly if some friends happen to accidentally meet in the street. The journey of an oversized key sculpture from the refugee camp Aida near Bethlehem to the 7th Berlin Biennale provided an occasion to address the marginalization of the Palestinian narrative within the German public. With the passport and postal stamps for Palestine that Khaled Jarrar distributes worldwide as part of his project State of Palestine, the artist suggests the existence of a hitherto utopian state while at the same time transcending stable national aspirations.

Among the numerous discussions of recent years about the relationship between art and social responsibility, Artur Żmijewski’s Berlin Biennale represents a decisive practical step forward, not least also in terms of addressing the kind of self-deception that “critical” art is subjected to. For where does critical art really make an impact? Does it change the regional grievances it points out, or does it matter rather in the western centers where it is not only shown, but economically profitable? The Institute for Human Activities, which was co-founded by the artist Renzo Martens, attempts to turn the tables by displacing art production to places where gentrification would actually be desirable. A program of workshops and stipends on a plantation in the Congo wants to encourage local residents to benefit from the global art market by producing their own artworks. The Institute launched its five-year plan of activities with a seminar conducted as part of the 7th Berlin Biennale.

These were just a few concrete examples among the many other thought-provoking 7th Berlin Biennale projects. The Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP), initiated by Israeli-Dutch artist Yael Bartana, calls for a return of more than 3 million Jews to Poland, opening up questions about issues of co-existence both regarding Europe and Israel and the Middle East. Held at the Hebbel am Ufer (HAU 1), the First International Congress of the JRMiP developed a concrete platform and demands for the movement. The New World Summit by Dutch artist Jonas Staal was another contribution to the culture of political debate. Organized at Sophiensaele, this event brought together political and legal representatives of organizations marked on international terrorist lists. Discussing the undemocratic methods with which democracies exclude certain interests from their systems of representation, the alternative “parliament” assessed possibilities for introducing a radical form of democracy in Europe.

Political engagement is always connected to the problem of social responsibility. Theater that Acts was developed in cooperation with the Hebbel am Ufer and one of its performances, Illumination, by the theater group Krétakör around Hungarian director Árpád Schilling, pledged for understanding actors as political people. The actors of Krétakör see themselves as active members of society who transcend “façade art” (Marcin Śliwa in the reader Forget Fear).

As part of our contemporary society it is particularly the Occupy movements (started in 2011 with M15 and Occupy Wall Street) that represent the demand for social empowerment and participation on a global scale in a media savvy manner. Throughout the duration of the 7th Berlin Biennale, representatives from these different international groups practiced their forms of protest and strategies of involvement on the ground floor of KW. While the institution initially only offered the space, over the course of the exhibition this partnership grew into the desire not only to address the visitors of the exhibition as members of society, but also to transform the institution as a mediator between art and society into a “horizontal” structure––an example of the process-based and self-critical methods with which Artur Żmijewski and his associated curators made pivotal contributions to contemporary discussions around exhibition production.

The 7th Berlin Biennale did not pursue the type of curatorial concept that communicates a particular idea through a physical arrangement of artworks in a space. Rather it was the question how art can allow citizens to influence reality and foster critical attitudes in society. Both the activists from the movements as well as the participating artists tried to position themselves in relation to concrete political and social concerns in order to contribute to situating art within the field of contemporary politics. At several moments during the 7th Berlin Biennale it became apparent how uncomfortable both art’s debate with itself and its confrontation with political reality can be. For an attitude of artistic and political responsibility is always accompanied by skepticism, disagreement, risk, confrontation, and possible failure. The 7th Berlin Biennale prompted us to leave behind our feelings of discomfort and fear of confrontations and change in order to face the challenge of social transformation.

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Morden Art

Modern art includes artistic works produced during the period extending roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, and denotes the style and philosophy of the art produced during that era.[1] The term is usually associated with art in which the traditions of the past have been thrown aside in a spirit of experimentation.[2] Modern artists experimented with new ways of seeing and with fresh ideas about the nature of materials and functions of art. A tendency toward abstraction is characteristic of much modern art. More recent artistic production is often called Contemporary art or Postmodern art.

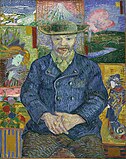

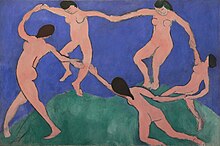

Modern art begins with the heritage of painters like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec all of whom were essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubist Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Henri Matisse's two versions of The Dance signified a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[3] It reflected Matisse's incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm color of the figures against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism.

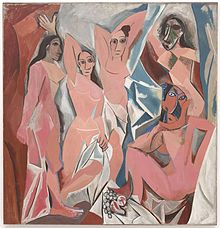

Initially influenced by Toulouse Lautrec, Gauguin and other late 19th century innovators Pablo Picasso made his first cubist paintings based on Cézanne's idea that all depiction of nature can be reduced to three solids: cube, sphere and cone. With the painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), Picasso dramatically created a new and radical picture depicting a raw and primitive brothel scene with five prostitutes, violently painted women, reminiscent of African tribal masks and his own new Cubist inventions. Analytic cubism was jointly developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, exemplified by Violin and Candlestick, Paris, from about 1908 through 1912. Analytic cubism, the first clear manifestation of cubism, was followed by Synthetic cubism, practised by Braque, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp and several other artists into the 1920s. Synthetic cubism is characterized by the introduction of different textures, surfaces, collage elements, papier collé and a large variety of merged subject matter.[citation needed]

The notion of modern art is closely related to Modernism.[4]

Although modern sculpture and architecture are reckoned to have emerged at the end of the 19th century, the beginnings of modern painting can be located earlier.[5] The date perhaps most commonly identified as marking the birth of modern art is 1863,[6] the year that Édouard Manet exhibited his painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe in the Salon des Refusés in Paris. Earlier dates have also been proposed, among them 1855 (the year Gustave Courbet exhibited The Artist's Studio) and 1784 (the year Jacques-Louis David completed his painting The Oath of the Horatii).[6] In the words of art historian H. Harvard Arnason: "Each of these dates has significance for the development of modern art, but none categorically marks a completely new beginning .... A gradual metamorphosis took place in the course of a hundred years."[6]

The strands of thought that eventually led to modern art can be traced back to the Enlightenment, and even to the 17th century.[7] The important modern art critic Clement Greenberg, for instance, called Immanuel Kant "the first real Modernist" but also drew a distinction: "The Enlightenment criticized from the outside ... . Modernism criticizes from the inside."[8] The French Revolution of 1789 uprooted assumptions and institutions that had for centuries been accepted with little question and accustomed the public to vigorous political and social debate. This gave rise to what art historian Ernst Gombrich called a "self-consciousness that made people select the style of their building as one selects the pattern of a wallpaper."[9]

The pioneers of modern art were Romantics, Realists and Impressionists.[10] By the late 19th century, additional movements which were to be influential in modern art had begun to emerge: post-Impressionism as well as Symbolism.

Influences upon these movements were varied: from exposure to Eastern decorative arts, particularly Japanese printmaking, to the coloristic innovations of Turner and Delacroix, to a search for more realism in the depiction of common life, as found in the work of painters such as Jean-François Millet. The advocates of realism stood against the idealism of the tradition-bound academic art that enjoyed public and official favor.[11] The most successful painters of the day worked either through commissions or through large public exhibitions of their own work. There were official, government-sponsored painters' unions, while governments regularly held public exhibitions of new fine and decorative arts.

The Impressionists argued that people do not see objects but only the light which they reflect, and therefore painters should paint in natural light (en plein air) rather than in studios and should capture the effects of light in their work.[12] Impressionist artists formed a group, Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs ("Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers") which, despite internal tensions, mounted a series of independent exhibitions.[13] The style was adopted by artists in different nations, in preference to a "national" style. These factors established the view that it was a "movement". These traits—establishment of a working method integral to the art, establishment of a movement or visible active core of support, and international adoption—would be repeated by artistic movements in the Modern period in art.

During the years between 1910 and the end of World War I and after the heyday of cubism, several movements emerged in Paris. Giorgio de Chirico moved to Paris in July 1911, where he joined his brother Andrea (the poet and painter known as Alberto Savinio). Through his brother he met Pierre Laprade, a member of the jury at the Salon d'Automne where he exhibited three of his dreamlike works: Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During 1913 he exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, and his work was noticed by Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, and several others. His compelling and mysterious paintings are considered instrumental to the early beginnings of Surrealism. Song of Love (1914) is one of the most famous works by de Chirico and is an early example of the surrealist style, though it was painted ten years before the movement was "founded" by André Breton in 1924.

World War I brought an end to this phase but indicated the beginning of a number of anti-art movements, such as Dada, including the work of Marcel Duchamp, and of Surrealism. Artist groups like de Stijl and Bauhaus developed new ideas about the interrelation of the arts, architecture, design, and art education.

Modern art was introduced to the United States with the Armory Show in 1913 and through European artists who moved to the U.S. during World War I.

By the end of the 1970s, when cultural critics began speaking of "the end of painting" (the title of a provocative essay written in 1981 by Douglas Crimp), new media art had become a category in itself, with a growing number of artists experimenting with technological means such as video art.[16] Painting assumed renewed importance in the 1980s and 1990s, as evidenced by the rise of neo-expressionism and the revival of figurative painting.[17]

Towards the end of the 20th century, a number of artists and architects started questioning the idea of "the modern" and created typically Postmodern works.[18]

Modern art begins with the heritage of painters like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec all of whom were essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubist Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Henri Matisse's two versions of The Dance signified a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[3] It reflected Matisse's incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm color of the figures against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism.

Initially influenced by Toulouse Lautrec, Gauguin and other late 19th century innovators Pablo Picasso made his first cubist paintings based on Cézanne's idea that all depiction of nature can be reduced to three solids: cube, sphere and cone. With the painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), Picasso dramatically created a new and radical picture depicting a raw and primitive brothel scene with five prostitutes, violently painted women, reminiscent of African tribal masks and his own new Cubist inventions. Analytic cubism was jointly developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, exemplified by Violin and Candlestick, Paris, from about 1908 through 1912. Analytic cubism, the first clear manifestation of cubism, was followed by Synthetic cubism, practised by Braque, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp and several other artists into the 1920s. Synthetic cubism is characterized by the introduction of different textures, surfaces, collage elements, papier collé and a large variety of merged subject matter.[citation needed]

The notion of modern art is closely related to Modernism.[4]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History of modern art

[edit] Roots in the 19th century

The strands of thought that eventually led to modern art can be traced back to the Enlightenment, and even to the 17th century.[7] The important modern art critic Clement Greenberg, for instance, called Immanuel Kant "the first real Modernist" but also drew a distinction: "The Enlightenment criticized from the outside ... . Modernism criticizes from the inside."[8] The French Revolution of 1789 uprooted assumptions and institutions that had for centuries been accepted with little question and accustomed the public to vigorous political and social debate. This gave rise to what art historian Ernst Gombrich called a "self-consciousness that made people select the style of their building as one selects the pattern of a wallpaper."[9]

The pioneers of modern art were Romantics, Realists and Impressionists.[10] By the late 19th century, additional movements which were to be influential in modern art had begun to emerge: post-Impressionism as well as Symbolism.

Influences upon these movements were varied: from exposure to Eastern decorative arts, particularly Japanese printmaking, to the coloristic innovations of Turner and Delacroix, to a search for more realism in the depiction of common life, as found in the work of painters such as Jean-François Millet. The advocates of realism stood against the idealism of the tradition-bound academic art that enjoyed public and official favor.[11] The most successful painters of the day worked either through commissions or through large public exhibitions of their own work. There were official, government-sponsored painters' unions, while governments regularly held public exhibitions of new fine and decorative arts.

The Impressionists argued that people do not see objects but only the light which they reflect, and therefore painters should paint in natural light (en plein air) rather than in studios and should capture the effects of light in their work.[12] Impressionist artists formed a group, Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs ("Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers") which, despite internal tensions, mounted a series of independent exhibitions.[13] The style was adopted by artists in different nations, in preference to a "national" style. These factors established the view that it was a "movement". These traits—establishment of a working method integral to the art, establishment of a movement or visible active core of support, and international adoption—would be repeated by artistic movements in the Modern period in art.

[edit] Early 20th century

Among the movements which flowered in the first decade of the 20th century were Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism.During the years between 1910 and the end of World War I and after the heyday of cubism, several movements emerged in Paris. Giorgio de Chirico moved to Paris in July 1911, where he joined his brother Andrea (the poet and painter known as Alberto Savinio). Through his brother he met Pierre Laprade, a member of the jury at the Salon d'Automne where he exhibited three of his dreamlike works: Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During 1913 he exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, and his work was noticed by Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, and several others. His compelling and mysterious paintings are considered instrumental to the early beginnings of Surrealism. Song of Love (1914) is one of the most famous works by de Chirico and is an early example of the surrealist style, though it was painted ten years before the movement was "founded" by André Breton in 1924.

World War I brought an end to this phase but indicated the beginning of a number of anti-art movements, such as Dada, including the work of Marcel Duchamp, and of Surrealism. Artist groups like de Stijl and Bauhaus developed new ideas about the interrelation of the arts, architecture, design, and art education.

Modern art was introduced to the United States with the Armory Show in 1913 and through European artists who moved to the U.S. during World War I.

[edit] After World War II

It was only after World War II, however, that the U.S. became the focal point of new artistic movements.[14] The 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of Abstract Expressionism, Color field painting, Pop art, Op art, Hard-edge painting, Minimal art, Lyrical Abstraction, FLUXUS, Postminimalism, Photorealism and various other movements. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, Land art, Performance art, Conceptual art, and other new art forms had attracted the attention of curators and critics, at the expense of more traditional media.[15] Larger installations and performances became widespread.By the end of the 1970s, when cultural critics began speaking of "the end of painting" (the title of a provocative essay written in 1981 by Douglas Crimp), new media art had become a category in itself, with a growing number of artists experimenting with technological means such as video art.[16] Painting assumed renewed importance in the 1980s and 1990s, as evidenced by the rise of neo-expressionism and the revival of figurative painting.[17]

Towards the end of the 20th century, a number of artists and architects started questioning the idea of "the modern" and created typically Postmodern works.[18]

[edit] Art movements and artist groups

(Roughly chronological with representative artists listed.)[edit] Roots of modern art

[edit] 19th century

- Romanticism the Romantic movement - Francisco de Goya, J. M. W. Turner, Eugène Delacroix

- Realism - Gustave Courbet, Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet

- Impressionism - Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley

- Post-impressionism - Georges Seurat, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau

- Symbolism - Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, James Ensor

- Les Nabis - Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton

- pre-Modernist Sculptors - Aristide Maillol, Auguste Rodin

[edit] Early 20th century (before World War I)

- Art Nouveau & variants - Jugendstil, Modern Style, Modernisme - Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt,

- Art Nouveau Architecture & Design - Antoni Gaudí, Otto Wagner, Wiener Werkstätte, Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, Koloman Moser

- Cubism - Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso

- Fauvism - André Derain, Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck

- Expressionism - Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde

- Futurism - Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà

- Die Brücke - Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

- Der Blaue Reiter - Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc

- Orphism - Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, Jacques Villon

- Photography - Pictorialism, Straight photography

- Post-Impressionism - Emily Carr

- Pre-Surrealism - Giorgio de Chirico, Marc Chagall

- Russian avant-garde - Kasimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov

- Sculpture - Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brâncuşi

- Synchromism - Stanton MacDonald-Wright, Morgan Russell

- Vorticism - Wyndham Lewis

[edit] World War I to World War II

- Dada - Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Francis Picabia, Kurt Schwitters

- Synthetic Cubism - Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso

- Pittura Metafisica - Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Giorgio Morandi

- De Stijl - Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian

- Expressionism - Egon Schiele, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine

- New Objectivity - Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz

- Figurative painting - Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard

- American Modernism - Stuart Davis, Arthur G. Dove, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O'Keeffe

- Constructivism - Naum Gabo, Gustav Klutsis, László Moholy-Nagy, El Lissitzky, Kasimir Malevich, Vadim Meller, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin

- Surrealism - Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall

- Bauhaus - Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Josef Albers

- Sculpture - Alexander Calder, Alberto Giacometti, Gaston Lachaise, Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, Julio Gonzalez

- Scottish Colourists - Francis Cadell, Samuel Peploe, Leslie Hunter, John Duncan Fergusson

- Suprematism - Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Lyubov Popova, Nikolai Suetin, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavskaya

- Precisionism - Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth

[edit] After World War II

- Figuratifs - Bernard Buffet, Jean Carzou, Maurice Boitel, Daniel du Janerand, Claude-Max Lochu

- Sculpture - Henry Moore, David Smith, Tony Smith, Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi,[19] Alberto Giacometti, Sir Anthony Caro, Jean Dubuffet, Isaac Witkin, René Iché, Marino Marini, Louise Nevelson

- Abstract expressionism - Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell

- American Abstract Artists - Ilya Bolotowsky, Ibram Lassaw, Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, Burgoyne Diller

- Art Brut - Adolf Wölfli, August Natterer, Ferdinand Cheval, Madge Gill, Paul Salvator Goldengreen

- Arte Povera - Jannis Kounellis, Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Piero Manzoni, Alighiero Boetti

- Color field painting - Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Sam Francis, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Helen Frankenthaler

- Tachisme - Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Ludwig Merwart

- COBRA - Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel, Asger Jorn

- De-collage - Wolf Vostell, Mimmo Rotella

- Neo-Dada - Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, John Chamberlain, Joseph Beuys, Lee Bontecou, Edward Kienholz

- Fluxus - George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, Daniel Spoerri, Dieter Roth, Carolee Schneeman, Alison Knowles, Charlotte Moorman, Dick Higgins

- Happening - Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Red Grooms, Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Robert Whitman, Yoko Ono

- Dau-al-Set - founded in Barcelona by poet/artist Joan Brossa, - Antoni Tàpies

- Grupo El Paso - founded in Madrid by artists Antonio Saura, Pablo Serrano

- Geometric abstraction - Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Nadir Afonso, Manlio Rho, Mario Radice, Mino Argento

- Hard-edge painting - John McLaughlin, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Al Held, Ronald Davis

- Kinetic art - George Rickey, Getulio Alviani

- Land art - Christo, Richard Long, Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer

- Les Automatistes - Claude Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Marcelle Ferron

- Minimal art - Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Agnes Martin

- Postminimalism - Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Lynda Benglis

- Lyrical abstraction - Ronnie Landfield, Sam Gilliam, Larry Zox, Dan Christensen, Natvar Bhavsar, Larry Poons

- Neo-figurative art - Fernando Botero, Antonio Berni

- Neo-expressionism - Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Transavanguardia - Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino, Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi

- Figuration libre - Hervé Di Rosa, François Boisrond, Robert Combas

- New realism - Yves Klein, Pierre Restany, Arman

- Op art - Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, Richard Anuszkiewicz

- Outsider art - Howard Finster, Grandma Moses, Bob Justin

- Photorealism - Audrey Flack, Chuck Close, Duane Hanson, Richard Estes, Malcolm Morley

- Pop art - Richard Hamilton, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, David Hockney

- Postwar European figurative painting - Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Gerhard Richter

- New European Painting - Luc Tuymans, Marlene Dumas, Neo Rauch, Bracha Ettinger, Michaël Borremans, Chris Ofili

- Shaped canvas - Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Ron Davis, Robert Mangold.

- Soviet art - Alexander Deineka, Alexander Gerasimov, Ilya Kabakov, Komar & Melamid, Alexandr Zhdanov, Leonid Sokov

- Spatialism - Lucio Fontana

- Video Art - Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Joseph Beuys, Bill Viola

- Visionary art - Ernst Fuchs, Paul Laffoley, Michael Bowen

[edit] Important modern art exhibitions and museums

- For a comprehensive list see Museums of modern art.

[edit] Belgium

[edit] Brazil

[edit] Colombia

[edit] Croatia

[edit] Ecuador

[edit] Finland

[edit] France

- Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art, Villeneuve d'Ascq

- Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris

- Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- Musée Picasso, Paris

- Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Strasbourg

[edit] Germany

- documenta, Kassel (Germany), a five-yearly exhibition of modern and contemporary art

- Museum Ludwig, Cologne

- Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

[edit] India

- National Gallery of Modern Art - New Delhi,

- National Gallery of Modern Art - Mumbai,

- National Gallery of Modern Art - Bangalore,

[edit] Iran

[edit] Italy

[edit] Mexico

[edit] Netherlands

[edit] Qatar

[edit] Spain

- Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

- Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia

[edit] Sweden

[edit] UK

[edit] U.S.A.

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

- Guggenheim Museum, New York City, New York & Venice, Italy ; more recently in Berlin, Germany, Bilbao, Spain & Las Vegas, Nevada

- High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

- McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas

- Menil Collection, Houston, Texas

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City, New York

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, New York

[edit] See also

- Modernism

- List of modern artists

- List of 20th-century women artists

- 20th century art

- 20th-century Western painting

- Art manifesto

- Art movements

- Art periods

- Contemporary art

- History of painting

- Modern architecture

- Postmodern art

- Western painting

[edit] Notes

- ^ Atkins 1990, p. 102.

- ^ Gombrich 1958, p. 419.

- ^ Russell T. Clement. Four French Symbolists. Greenwood Press, 1996. Page 114.

- ^ "One way of understanding the relation of the terms 'modern,' 'modernity,' and 'modernism' is that aesthetic modernism is a form of art characteristic of high or actualized late modernity, that is, of that period in which social, economic, and cultural life in the widest sense [was] revolutionized by modernity ... [this means] that modernist art is scarcely thinkable outside the context of the modernized society of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Social modernity is the home of modernist art, even where that art rebels against it." Cahoone 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Arnason 1998, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Arnason 1998, p. 17.

- ^ "In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries momentum began to gather behind a new view of the world, which would eventually create a new world, the modern world". Cahoone 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Frascina and Harrison 1982, p. 5.

- ^ Gombrich 1958, pp. 358-359.

- ^ Arnason 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Corinth, Schuster, Brauner, Vitali, and Butts 1996, p.25.

- ^ Cogniat 1975, p. 61.

- ^ Cogniat 1975, pp. 43–49.

- ^ CIA and AbEx Retrieved November 7, 2010

- ^ Mullins 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Mullins 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Mullins 2006, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Post-Modernism: The New Classicism in Art and Architecture Charles Jencks

- ^ David Lander "Fifties Furniture: The Side Table as Sculpture," American Heritage, Nov./Dec. 2006.

[edit] References

- Arnason, H. Harvard. 1998. History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography. Fourth Edition, rev. by Marla F. Prather, after the third edition, revised by Daniel Wheeler. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3439-6; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-183313-8; London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23757-3 [Fifth edition, revised by Peter Kalb, Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall; London: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2004. ISBN 0-13-184069-X]

- Atkins, Robert. 1990. Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 1-55859-127-3

- Cahoone, Lawrence E. 1996. From Modernism to Postmodernism: An Anthology. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell. ISBN 1-55786-603-1

- Cogniat, Raymond. 1975. Pissarro. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-52477-5.

- Corinth, Lovis, Peter-Klaus Schuster, Lothar Brauner, Christoph Vitali, and Barbara Butts. 1996. Lovis Corinth. Munich and New York: Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-1682-6

- Frascina, Francis, and Charles Harrison (eds.) 1982. Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology. Published in association with The Open University. London: Harper and Row, Ltd. Reprinted, London: Paul Chapman Publishing, Ltd.

- Frazier, Nancy. 2001. The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051420-1

- Gombrich, E. H. 1958. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon. OCLC 220078463

- Mullins, Charlotte. 2006. Painting People: Figure Painting Today. New York: D.A.P. ISBN 978-1-933045-38-2

[edit] Further reading

- Adams, Hugh. 1979. Modern Painting. [Oxford]: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-1984-0 (cloth) ISBN 0-7148-1920-4 (pbk)

- Childs, Peter. 2000. Modernism. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19647-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-415-19648-5 (pbk)

- Crouch, Christopher. 2000. Modernism in Art Design and Architecture. New York: St. Martins Press. ISBN 0-312-21830-3 (cloth) ISBN 0-312-21832-X (pbk)

- Dempsey, Amy. 2002. Art in the Modern Era: A Guide to Schools and Movements. New York: Harry A. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4172-4

- Hunter, Sam, John Jacobus, and Daniel Wheeler. 2004. Modern Art. Revised and Updated 3rd Edition. New York: The Vendome Press [Pearson/Prentice Hall]. ISBN 0-13-189565-6 (cloth) 0-13-150519-X (pbk)

- Kolocotroni, Vassiliki, Jane Goldman, and Olga Taxidou (eds.). 1998. Modernism: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45073-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-226-45074-0 (pbk)

- Ozenfant, Amédée. 1952. Foundations of Modern Art. New York: Dover Publications. OCLC 536109

- Read, Herbert and Benedict. 1975. A Concise History of Modern Painting. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20141-1

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)